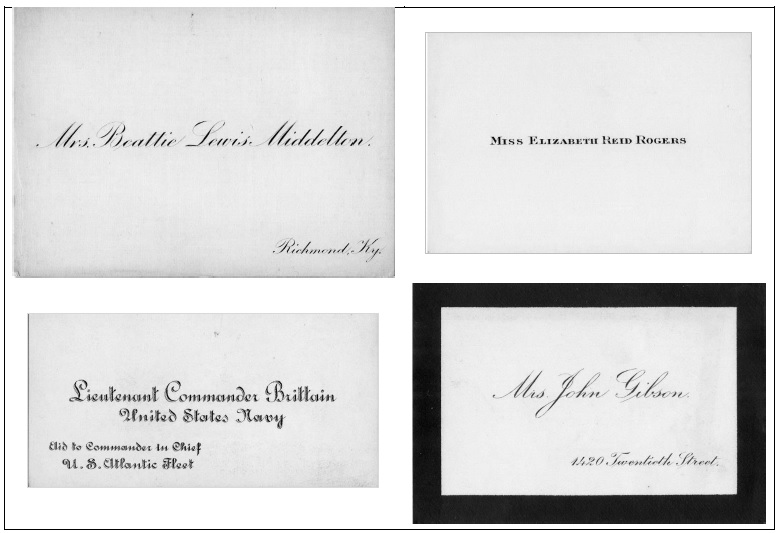

To move up in society in the 19th century, men and women needed personalized calling or visiting cards. These small cards, about the size of a modern-day business card, usually featured the name of the owner, and sometimes an address. Calling cards were left at homes, sent to individuals, or exchanged in person for various social purposes. Knowing and following calling card “rules” signaled one’s status and intentions.

Calling cards were just one of many rules of etiquette governing how to interact with friends and new acquaintances. Rules of etiquette, or manners, are social rituals that vary widely over time and place. But whatever the rules, those wanting to move from a lower or middle class or status to a higher social rank had to learn and follow the rules to be socially accepted.

“A bit of pasteboard, bearing the name of a person, is, in itself, of course, a very trivial affair. But all the formalities and social observances of well-bred people have a special significance, among such people, and no means of the interchange of civilities holds a superior place to the visiting card. Its language is as deeply significant as that of any other sign-language, and there is a right way to use it as well as a wrong way -a grammatical as well as an ungrammatical way.” (Etiquette of Visiting Cards by Mrs. L. N. Howard, 1880

Before the 18th century, visitors making social calls left handwritten notes at the home of friends who were not at home. By the 1760s, the upper classes in France and Italy were leaving printed visiting cards decorated with images on one side and a blank space for hand-writing a note on the other. The style quickly spread across Europe and to the United States. As printing technology improved, elaborate color designs became increasingly popular.

Elaborate visiting cards fell out of style in the late 1800s. New rules dictated plain cards with an elegantly printed name. In 1889, one author noted a visiting card’s “tint, texture, and engraving are witnesses to its owner’s habits and to his knowledge of the most approved customs in the social world.” (Their Significance and Proper Uses, as Governed by the Usages of New York Society by Abby Buchanan Longstreet, 1889.)

Almost every 19th and early 20th-century etiquette book addressed the rules of paying visits and calling cards. Experts dictated not just what type of card to carry, but every aspect of social interaction. Even the furnishings in the entryway of homes had to be considered. To follow this advice given below, one needed far more than just calling cards. Servants, homes large enough to include a parlor, and a card receiver basket were also required. In other words, this level of social etiquette required money and leisure time.

When the servant answers your ring, hand in your card. If your friend is out or engaged, leave the card, and if she is in, send it up. Never call without cards. You may offend your friend, as she may never hear of your call, if she is out at the time, and you trust to the memory of the servant.

If your friend is at home, after sending your card up to her by the servant, go into the parlor to wait for her. Sit down quietly, and do not leave your seat until you rise to meet her as she enters the room. To walk about the parlor, examining the ornaments and pictures, is ill- bred. It is still more unlady-like to sit down and turn over to read the cards in her card basket. If she keeps you waiting for a long time, you may take a book from the center-table to pass away interval. (The Ladies’ Book of Etiquette and Manual of Politeness by Florence Hartley, 1873)

By 1922, manners expert Emily Post acknowledged the Victorian use of the visiting card, “left as evidence of one person’s presence at the house of another” was going out of style in fashionable circles.” Yet, she advised that one still needed printed cards because, “in New York, for instance, the visiting card has entirely taken the place of the written note of invitation to informal parties of every description. Messages of condolence or congratulation are written on it; it is used as an endorsement in the giving of an order; it is even tacked on the outside of express boxes.”

Even though times seemed to be changing, Post advised “The personal card is in a measure, an index of one’s character. A fantastic or garish note . . . betrays a lack of taste in the owner of the card.” (Etiquette in Society, in Business, in Politics and at Home by Emily Post, 1922)

What has replaced 19th-century parlors and calling cards?

Visiting cards and old etiquette books are reminders for how acceptable behavior changes across time and social class.

- What are the “rules” for visiting today?

- What other forms of social interaction have replaced visiting? For example, is dining out more important socially than visiting in homes?

- Are rules of etiquette the same for people of all ages and social status?

- Visiting cards no longer communicate one’s taste and status; what are the new markers and symbols of one’s taste and character?

- Most modern homes are not equipped with servants, parlors and card receivers; what has taken the place of these markers of social status?

To learn more . . .

- For about the history of daily life and classroom ideas and activities, see Exploring Vacation and Etiquette Themes in Social Studies and Investigating Family, Food, and Housing Themes in Social Studies.

- See “Visiting Cards” for more images and information.

About the Header Image: Visiting Cards, 1909. The black border (card on the bottom left) indicated the person was in mourning because of the death of a family member. Courtesy of Eastern Kentucky University Special Collections and Archives, Richmond, KY.

In a world of email, the address on a calling card seems out of place. A fun image to use on lessons on how to write a polite letter or email.

Teaching manners is important in a 3rd or 4th grade classroom. I could use these images of calling cards in lesson on how to introduce yourself when meeting new people.