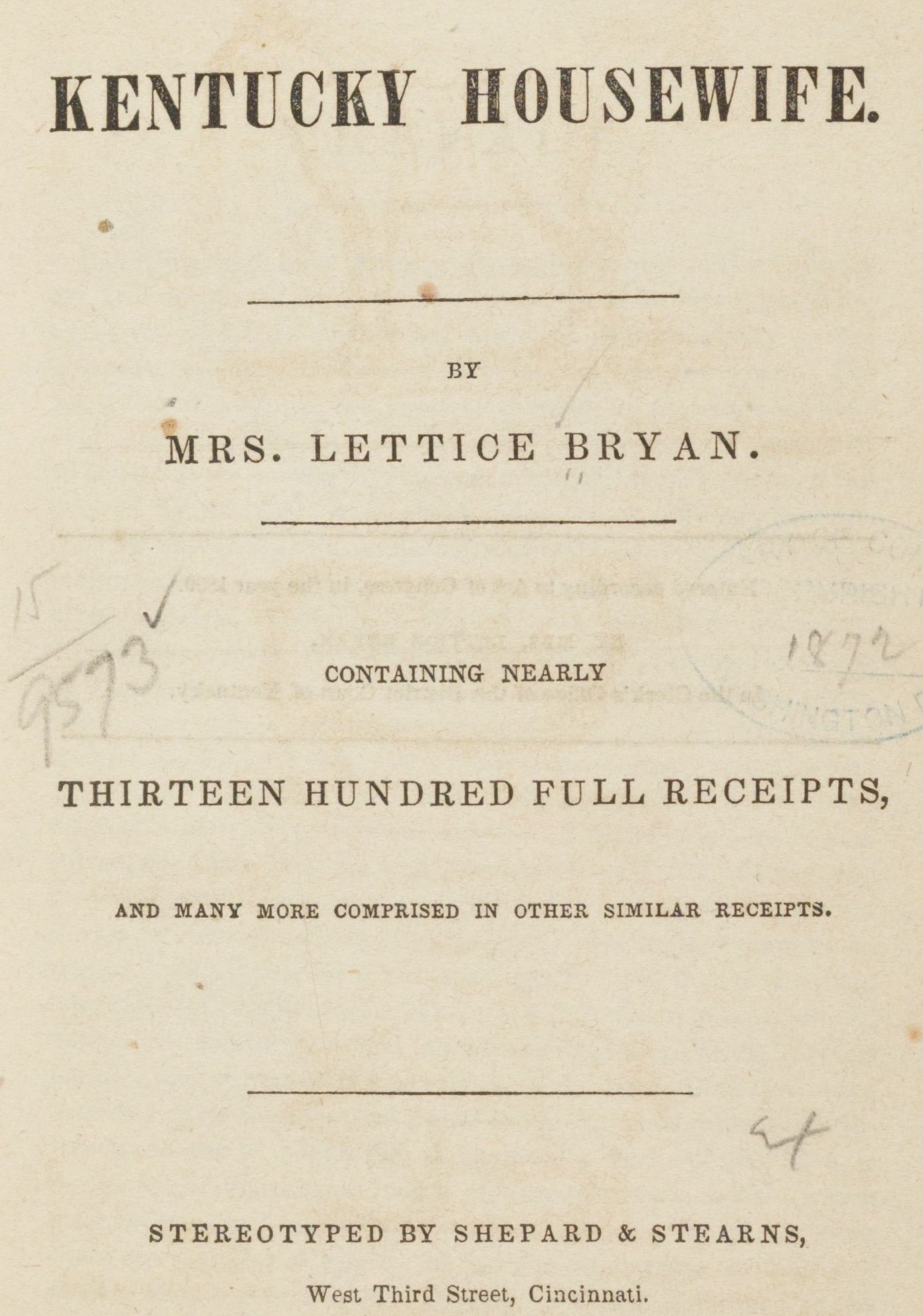

Old recipe books tell the story of the daily routine of average women in the past. Lettice Pierce Bryan (1805-1877), the author of The Kentucky Housewife, was one of those women. Her collection of “receipts” for food and more illustrate key lessons about running a household in the pre-industrial era.

A quick history of cookbooks before The Kentucky Housewife

Cookbooks are collections of recipes and other advice for preparing food. The word cookbook originated in the United States in 1809, a simplification of the English term cookery-book used as far back as 1639. The word recipe derived from the word receive. In historical sources, recipes are often referred to as receipts, reflecting the concept that advice and instructions are received from others.

Select the images for a larger view.

Collections of recipes in the ancient and medieval world usually described dishes consumed by the elite and were products of wealthy households. Even though recipe collections have survived from these eras, most cooks learned through practice in a kitchen. As cooks (mostly women) completed this daily household routine, children, (mostly girls) watched and assisted. Even in the kitchens of the wealthy, cooks, working as slaves or paid servants, learned by example or through apprenticeships, not by reading instructions or cookbooks.

With the growth of printing and literacy in the 18th century, printed cookbooks became more common. The earliest cookbooks in colonial America were imported copies or American reprints of English cookbooks. Many of these early printed cookbooks contained much more than instructions for preparing food. Instructions for preserving fruits, vegetables, and meats; recipes for cosmetics, and guidance and remedies for every aspect of household management and home medical care were included.

The first American cookbooks

Not until 1796, twenty years after the American Revolution, did the first truly American cookbook appear, named American Cookery. Little is known about the author, Amelia Simmons. The book was inexpensive and included both practical, everyday recipes as well as those intended for special occasions. Many of the recipes were borrowed from British cookbooks, but others incorporated uniquely American ingredients. For example, Simmons included receipts (recipes) using uniquely American ingredients – cornmeal, crookneck squash, Jerusalem artichoke, cranberries, and watermelon. She also included original recipes for “Pompkin” puddings, the forerunner of the modern pumpkin pies, and unique American approaches to traditional English dishes such as “minced” or mincemeat pies and gingerbread.

America’s first widely popular cookbook to describe unique regional dishes was Mary Randolph’s The Virginia House-Wife (1824), reprinted at least nineteen times before the Civil War. Mrs. Bryan’s The Kentucky Housewife (1839) was another early cookbook featuring regional dishes.

The Kentucky Housewife contains more than 1300 recipes for foods with distinctly American ingredients such as turkey, cranberries, corn and, shote. Many of the recipes had African and Native American origins. Recipes and advice for preserving foods such as pickles and catsups and making “liquors” such as wine and fruit cordials are included. Mrs. Bryan also included numerous recipes for food and remedies for the sick, recipes for cosmetics and perfume, and “miscellaneous receipts” for cleaning products and performing other household chores.

History lessons from old recipe books

American cookbooks such as The Kentucky Housewife were different from modern cookbooks in several ways. First, cookbook authors such as Mrs. Bryan assumed the reader had a basic knowledge of cooking using the technology of the era – a hearth, and later, the wood-fired stove. She assumed readers would understand the often vague measurements and instructions. Second, measurements for ingredients such as handfuls, spoonfuls, a small quantity, or a tea-cupful are vague by modern standards. The standardized measures used in modern cookbooks, such as teaspoons, tablespoons, and cups, did not come into common use until the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Third, Mrs. Bryan and other early cookbook authors expected that most ingredients would be raised at home or obtained locally, evidence of the agrarian nature of the early American economy. Industrially processed and packaged foods available at grocery stores were not available at the time her work was published.

Finally, in the introductory pages of her cookbook, Mrs. Bryan assumed that her readers were wives with domestic workers to help with the hard and never-ending work of the pre-industrial kitchen and home. These workers may have been paid help or slaves. According to her introduction, her volume of household advice was designed to promote the smooth running of the household, the welfare of the domestic workers, as well as allowing the mistress of the household to impress guests. She noted that following her advice would “bind up a lasting treasure of the rich and secure a plentiful living to the poor.” p. viii, The Kentucky Housewife.

Early American cookbooks are historical primary sources for more than food traditions. The advice between the covers and the stories of their authors illustrate the challenges of managing a household in a pre-industrial era. Lettice Bryan, the author of The Kentucky Housewife, wrote and published her cookbook while managing a household in Monticello, Kentucky with a husband and nine young children. While she was having children, running the household, and writing her book, her husband, Edmund Bryan, was training to be a physician. In the years following the publication of The Kentucky Housewife, her family moved at least twice, living in Washington County and Grayson County, Kentucky. She had a total of 14 children and died at age 72 in the home of a daughter and son-in-law. In 1885, Mrs. Bryan was said to be “a woman of an unusually fine presence, and well educated” for the time.

To learn more . . .

For more about the history of daily life, primary sources, and instructional activities by this author:

I could use this to teach a women’s history lesson in fifth grade. I would use the image of the Kentucky Housewife cookbook to teach students the roles of women in the 1800’s.