Utopias are usually imaginary places of perfection and limitless possibilities. Most utopian visions live in our minds, fictional literature, and art. However, in the late 19th century, fiction inspired very real utopian communities. The stories of Rugby, Tennessee; Kaweah, California; Ruskin Colony, Tennessee; and Equality Colony, Washington began with novels.

Rugby, Tennessee

Select the images for a larger view and more information.

Rugby, located in north-central Tennessee’s Morgan County, was the utopian dream of Thomas Hughes (1822-1896), an English judge, reformer, and novelist. Funds to establish the village came from the sales of Hughes’ novel, Tom Brown’s School Days (1857). The story recounted an upper-middle-class boy’s experience in the 1830s at the private English boarding school Rugby. The book was based on the author’s experiences at the school and the influence of his admired headmaster. The main character, Tom, became a model for an ideal gentleman of his social class – physically fit, moral, and caring. Hughes’s books were incredibly popular and numerous sequels followed.

In 1880, Hughes purchased 35,000 acres in Morgan and Scott County, Tennessee in conjunction with the London and Boston Boards of Aid to Land Ownership and named it after

his beloved school. Hughes imaged his community would become a haven for the upper-middle-class young men educated in English private schools with the manners and attitudes of gentlemen, but lacking family money to live without working. In England, these young men often lacked specialized training for a career, but were unwilling to take a working-class job “in trade.” Hughes hoped these men would create a new, productive life in America, free from English social class expectations.

Rugby attracted around 200 people in 1880 and by 1884 had around 400 residents. About half were English and half American but only about 9% were the single young men from England Hughes had expected. At its peak, the village in rural Tennessee had a newspaper (The Rugbeian), stores, a school, church, and a 7,000 volume library. The impressive Tabard Inn (named after the inn from which the pilgrims in Canterbury Tales began their journey), provided accommodations for “health and pleasure seekers.”

While Hughes was active in the Christian socialist reform movement in England, Rugby was never a socialist community where village members owned property communally. The “cheap farming lands” advertised were purchased by individuals and privately owned. Village residents could invest in “associations” or joint-stock enterprises. The general store operated in this manner for several years. But other joint-stock financial enterprises failed such as the tomato cannery and planned Rugby Pottery Company.

The utopian community grew for a few years but the lack of a successful financial plan and strong leadership were problematic. Rugby was labeled as unhealthy by the press after seven residents died from an 1881 typhoid epidemic. In 1887, Hughes returned to England after losing $250,000 on his utopian experiment. The land was purchased by a private American company in 1899, but the village continued to exist. Historic Rugby welcomes modern tourists.

Bellamy Communities

The novel Looking Backward: 2000–1887 by Edward Bellamy (1850-1898) inspired numerous communities and clubs across America in the late 19th century. The hero of the novel, Julian West, falls asleep under the influence of a mesmerist in 1887 and wakes up to a different world in the year 2000. In this new social order, through non-violent means, America’s citizens have overthrown the powerful business trusts of the late 19th century. Everyone works in an “industrial army” in a system called Nationalism. The business of the nation is owned by the people and their government. All citizens receive an adequate income that provides for their needs. The success of the cooperatively owned businesses provides ample funds for free education, parks, public services, and a leisurely retirement at age 45. Women and men are “equal” (at least as equal as the book’s 19th-century author could imagine) but perform different work suited to their “natures.” Fabulous new technology makes work easier and life more pleasant. Everything is so perfect, the United States no longer requires laws, politics, or a criminal justice system.

Nationalism, the name for Bellamy’s proposed social system, wasn’t drastically different from the model proposed by Karl Marx. However, Bellamy rejected Karl Marx’s model of socialism with class conflict and revolution. He claimed he had never even read the work of Marx. Bellamy’s vision for a communal society on a national scale especially appealed to a middle-class audience frustrated with the economic dominance of the late 19th-century robber barons as well as the angry workers.

The book quickly became a best seller and by 1891, followers established 165 clubs across the nation to promote the ideals described in the novel. Most of these clubs, named Nationalist Clubs, were political in nature. Members hoped to implement the novel’s governing and economic concepts in the real world. Nationalist clubs declined by the turn of the century, but their ideals influenced the American Populist Party and Eugene Debs and the Socialist Party of America.

Looking Backward also inspired several real-life communities. The novel was one of the inspirations for the Ruskin Cooperative Association or Ruskin Colony in Dickson County, Tennessee. This community was founded by labor journalist Julius Wayland in 1894. Around 250 members hoped for a better life and contributed $500 to join the community that promised a communal dining hall and laundry, housing, medical care, education, equality, and job security.

But like many utopian communities, the Ruskin Colony lacked clear goals to create a cohesive society out of its diverse members and a successful business plan. In 1899, a small group of Ruskin’s members forced the sale of the property and those who hoped to continue the community were unable to repurchase the land.

Equality Colony, named after Bellamy’s sequel novel published in 1897, was established in Skagit County, Washington in 1897 and flourished for a few years as a communal society. Bellamy Cooperative Colony was founded the same year in Lincoln County, Oregon by a group of mostly Norwegian settlers. Kaweah, in central California, was founded in 1886, had around 150 members at its peak, but disbanded six years later.

In the classroom

Ask your students to consider the essential question “How are utopian dreams a reflection of their time and culture?” Rugby and the Bellamy communities reflected concerns with the social, political, economic, and technological changes of their eras. New technology and industrialization were changing the social structure, everyday life, and the workplace. New political and economic ideas emerged in the 19th century, threatening the status quo. Rugby rejected socialism; the Bellamy communities embraced it but refused the violent version described by Karl Marx.

In the 21st century, dystopian fiction is far more common. Books, television shows, and movies depict worlds where everything is as bad as possible. In these dystopias, diseases spread, disasters occur, and modern technology goes wrong. How are modern dystopias reflecting the fears of our age? What are the utopian alternatives for the 21st century?

Resources:

Plan a visit to historic Rugby and support its historical preservation

Plan a visit to historic Rugby and support its historical preservation- Photographs of historic Rugby – Tennessee State Library and Archives

- Photographs of Ruskin Cooperative Association

- To learn more about the history of utopias: Discovering Quacks, Utopias, and Cemeteries, Modern Lessons from Historical Themes

- Related blog post: Classroom Management Tips: Lessons from Historical Utopias

References:

- Clay Bailey, “Looking Backward at the Ruskin Cooperative Association,” Tennessee Historical Quarterly, Vol. 53, No. 2 (Summer 1994), pp. 100-113

- Calvin Dickinson, “Radical Hillbillies, Socialism in Tennessee,” in Rural Life and Culture in the Upper Cumberland, Edited by Michael E. Birdwell and W. Calvin Dickinson. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2004.

- James J. Kopp and J. A. Dean, “Looking Backward at Edward Bellamy’s Influence in Oregon, 1888-1936,” Oregon Historical Quarterly, Vol. 104, No. 1 (Spring 2003), pp. 62-95.

- Brian L. Stagg, “Tennessee’s Rugby Colony,” Tennessee Historical Quarterly, Vol. 27, No. 3 (Fall 1968), pp. 209-224.

- Barbara Stagg, Historic Rugby, Arcadia Publishing 2007.

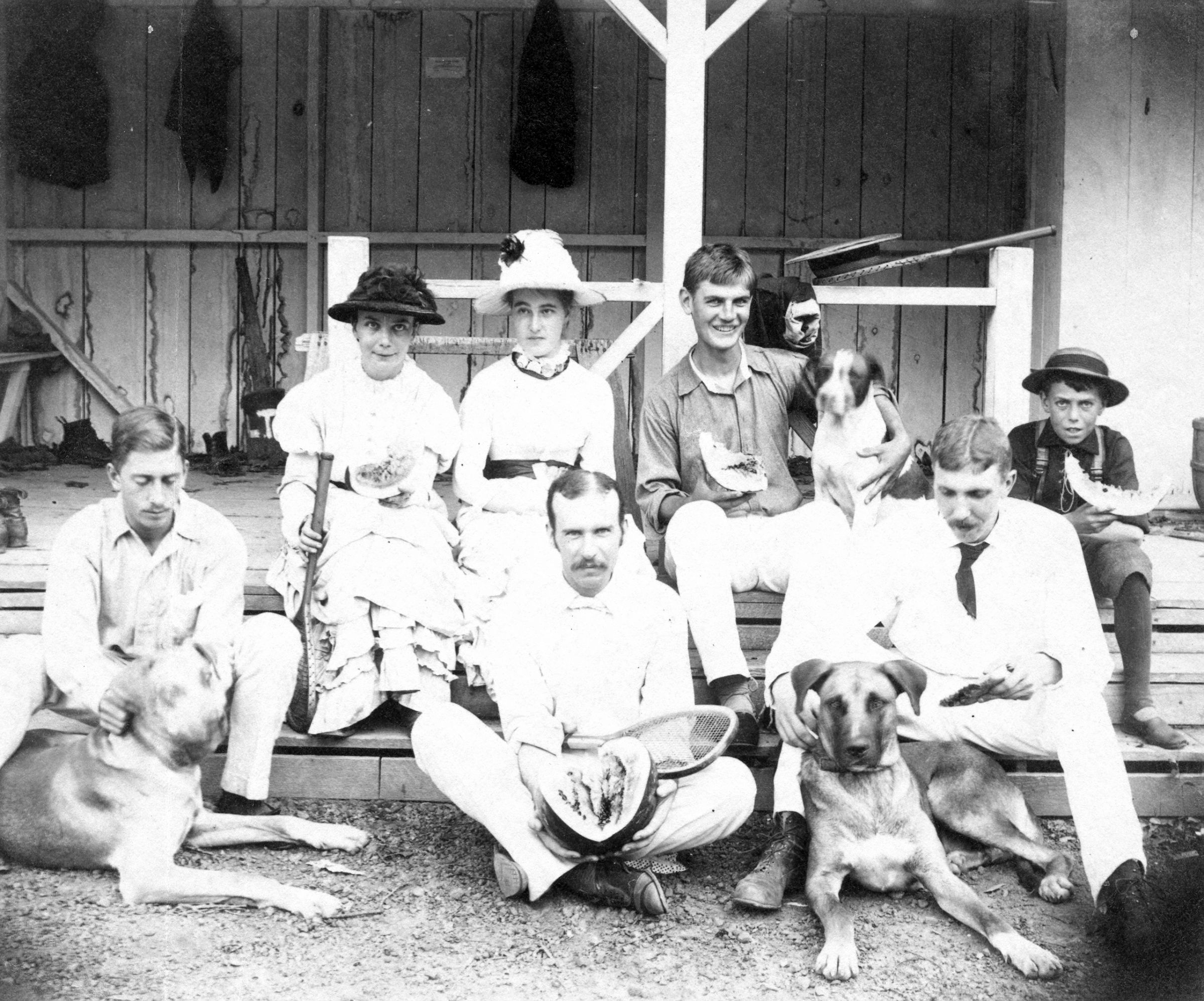

About the header image:

Men and women of Rugby Community in front of the Rugby Lawn Tennis Association clubhouse, 1880s. Historic Rugby welcomes visitors today. Like many other historic communitarian sites, the village is dedicated to preservation and education. Courtesy of Historic Rugby Inc.