Dragons are everywhere in 21st-century popular culture: books, movies, novels, games, and decorative arts. Dragons are also historical, roaming in cultures throughout the world since ancient times. They fly, slither, and swim in the folklore and myths of past cultures in the Americas, Africa, the Near and Far East, India, and Europe. However, when it comes to dragons, history does not always repeat itself. Modern dragons may appear similar to those from the past, but their uses and meanings vary, reflecting the beliefs of the culture that spawned them.

Select the images for a larger view and more information.

Historical dragons were chimerical beasts, illusory or impossible, formed from parts of other animals and descriptions of various authors. They could have two or four legs, be with or without wings or horns, and have skin covered with scales or hairs or feathers. Their tails come in endless varieties. Snakes or serpents or worms (wyverns) could also be dragons.

Until modern times, dragons were evil and dangerous. They killed and ate humans, strangled animals as large as elephants with their tails, and destroyed communities with poison or fire. Dragons had to be killed, defeated by gods, saints, angels, or mortal heroes and heroines.

Medieval Dragons

The European Middle Ages was full of dragons. Edward Topsell summarized what was known about winged dragons by ancient and medieval writers in The History of Four-footed Beasts and Serpents (1658)

There are some Dragons which have wings and no feet, some again have both feet and wings, and some neither feet nor wings, but are only distinguished from the common sort of Serpents by the comb growing upon their heads, and the beard under their cheeks. St. Augustine saith that Dragons abide in deep Caves and hollow places of the earth, and that sometimes when they perceive moisture in the air, they come out of their holes & beating the air with their wings, as it were the strokes of oars, they forsake the earth and fly aloft. Their wings are of a skinny substance, and very voluble, and spreading wide.

Medieval dragons appeared in several different sources, their qualities often merging or conflicting. The Bible and teachings of the medieval Church, bestiaries, travelers’ accounts, and, Greek and Roman myths, and European folk tales were all inhabited with dragons.

Dragons were mentioned in medieval editions the Bible in Psalm 148:7, Job 30:29, and Jeremiah 9:11. Scholars have determined the Latin term “draco,” meaning a large snake or dragon, was used for mistranslations of two different animals: a desert-dwelling jackal and a sea creature. Modern translations of the Bible do not feature dragons.

Medieval dragons were featured in religious stories and illustrations of St. Michael and the Apocalypse, Saint Margaret, and Saint George. George was the prototype for knights on quests to slay dragons, literal and figurative.

Dragons in The Beastiary or Book of Beasts

Bestiaries, or books of beasts, are illustrated collections of information about animals. The animals included were real and fantastic. These medieval works were based on a 2nd century A.D. work, the Physiologus (The Naturalist), which may have originated in Alexandria, Egypt. Medieval authors followed this model, compiling information from ancient Near Eastern, Greek, and Roman sources, Christian writers, myth, folklore, and observation. A medieval bestiary included more than just “facts” about the animals. The authors explained the symbolic and theological significance of each animal in Christianity. Dragons were closely associated with Satan, serpents, and devils and dangerous to both human life and salvation.

Beastiares were reference books in the Middle Ages. The information and images about dragons, serpents, snakes, and worms (wyverns) in bestiaries were frequently referenced by medieval naturalists, artists, writers. While production of bestiary manuscripts in Latin peaked in the 12th and 13th centuries, versions written in local or vernacular languages continued to be popular. In the 15th century, animal stories drawing from the old texts as well as new sources with woodcut pictures were printed with the new technology of the age, the printing press. Books about animals continue to be popular in the 21st century.

Dragons in travel accounts, folklore, and ancient myth

Descriptions of exotic beasts, including dragons, appeared in the accounts of travelers from ancient times to the early modern world. Many of these descriptions were lifted from the work of bestiaries, tales, and myths by “travel” writers who never left their desks. Others may have witnessed animals unknown in their own culture and labeled them with the names of familiar animals. For example, the 13th-century traveler Marco Polo mistook a rhinoceros for a unicorn. He reported dragons in southwest China, but it is likely what he really saw (or copied from other texts) was a crocodile.

Here are seen huge serpents, ten paces in length, and ten spans in the girt of the body. At the forepart, near the head, they have two short legs, having three claws like those of a tiger, with eyes larger than a fourpenny loaf (of bread) and very glaring. The jaws are wide enough to swallow a man, the teeth are large and sharp, and their whole appearance is so formidable, that neither man, nor any kind of animal, can approach them without terror (Chapter 40)

The mysterious author of the 13-century Travels of Sir John Mandeville described a desert “full of dragons and great serpents, and full of diverse venomous beasts all about” in Babylon, guarding the Tower of Babel. The Tower of Babel was well known to medieval Christians from its description in the Biblical text of Genesis.

Medieval texts and illustrations also related classical and folk tales of dragons. Melusine, from European folklore, was often depicted as a serpent, fish, or dragon. Beowulf killed a dragon. A dragon or serpent guarded the sacred spring of Ares, near Thebes in ancient Greece. A hundred-headed dragon named Ladon guarded the goddess Hera’s Golden Apples in the Garden of Hesperides. Jason and the Argonauts faced the dragon that guarded the Golden Fleece in a distant land.

Dragons: A new image for a new era

The revival of Greek and Roman myths in the Renaissance helped to rehabilitate dragons from symbols of evil to guardians of treasure and virtue. Dragons became popular symbols for coats of arms, illustrating the virtue of the family. At the same time, some Renaissance scholars argued dragons were mythical beasts and did not actually exist in the real world. Dragons appeared less frequently in the reports of early modern explorers. The evil medieval dragons faded in the face of newly imported Chinese dragons, symbols of good luck, strength, and power. By the 18th century, Samuel Johnson described a dragon as a violent, fierce man or woman, not an evil reptile.

Twentieth and 21st-century dragons sometimes resemble their ancestors, but most have taken on new identities in modern myths – fantasy and science fiction. Smaug, the dragon in J. R. R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit (1937) resembled his medieval ancestors – wicked, fire-breathing guardians of treasure. Tolkien was also a medieval historian, so his 20th-century dragon resembled its medieval predecessors.

On the other hand, most modern dragons are the friends and allies of humans and have lost their religious significance. The dragons in J. K. Rowling’s Harry Potter books are dangerous, but not evil. The science-fiction dragons of Pern in Anne McCaffery’s popular novels and the dragon-like creatures of Avatar are worthy steads. Daenerys Targaryen’s dragons in Game of Thrones and dragons in How to Train Your Dragon movies and books by Cressida Cowell are trainable creatures much like dogs, serving the good or bad nature of their human masters, not the gods.

History of dragons in the classroom

Even though dragons are not “real” history, their story can be used to illustrate how popular images, symbols, and stories reflect the culture of different times and places. While we recognize creatures called dragons described or depicted in historical sources, their purposes and qualities have shifted. Medieval dragons symbolized evil; modern dragons are the allies and companions of humans. Exploring those differences is key to understanding people in the past.

Dragons continue to be chimerical; they are composed of bits and pieces of past historical eras along with very modern and secular beliefs about good, evil, and animals. Ask your students to compare and contrast the 21st-century examples of dragons and their purpose to those of other cultures and times. Does history really repeat itself or do we just recycle, redefine, and reuse the past to tell a modern story?

Test your knowledge

Test your knowledge of strange and mythical beasts with this short quiz.

Read more by this author:

- Discovering Quacks, Utopias, and Cemeteries, Modern Lessons from Historical Themes

- Investigating Family, Food, and Housing Themes in Social Studies

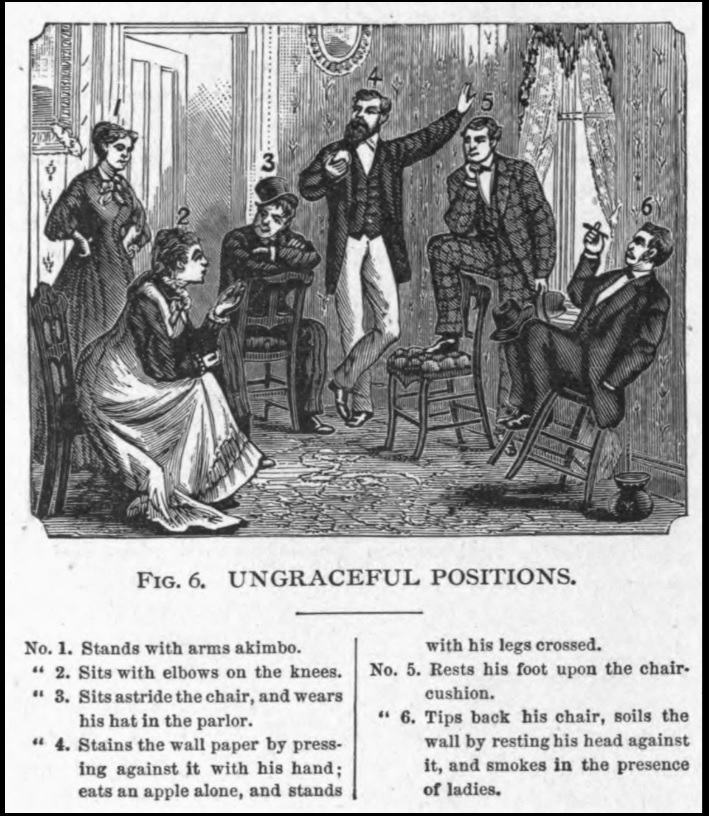

- Exploring Vacation and Etiquette Themes in Social Studies

References:

- Louise W. Lippincott, “The Unnatural History of Dragons,” Philadelphia Museum of Art Bulletin, Vol. 77, No. 334, (Winter, 1981), pp. 2-24.

- Sandra Unerman, “Dragons in Twentieth-Century Fiction,” Folklore, Vol. 113, No. 1 (Apr., 2002), pp. 94-101

- Willene B. Clark and Meradith T. McMunn, Beasts and Birds of the Middle Ages: The Bestiary and Its Legacy. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1989.

- “dragon, n.1”. Oxford English Dictionary Online.

I really enjoyed reading this article! I could use this to teach about the Middle Ages later elementary grades, such as fourth or fifth grade. I would use the images to begin the lesson in both an art and social studies lesson. The other lesson I think would be interesting would be about 21st-century fictional characters with medieval origins. There are many dragons in movies, books, and other literary works and students should understand the historical context behind the introduction of these characters and creatures.

I could use this in a lesson on the Middle Ages to compare the past to the present. Kids love dragons today but would have been afraid of them in the Middle Ages. I would use medieval illustrations to teach how medieval dragons were viewed.