Before the 1800s, baking in most homes was a challenge. As far back as ancient Mesopotamia, Egypt, Greece, and Rome, most people purchased baked products, mainly breads, from a professional baker. Only the wealthiest households had wood-fired enclosed ovens. Other daily home cooking was done on an open fire. Sweet baked goods like cake and cookies were rare and expensive in Europe until the 17th century when European colonization of the Americas and sugar plantations powered by enslaved people lowered the price of sugar.

However, colonial Americans were often far from a town with a professional baker and prepared simple breads and daily meals at a wood-fired hearth. The enclosed cookstove that made baking easier was invented in the early 1800s. However, its cost, weight, and bulk make it a luxury product on the frontiers of the United States.

Hearth Baking in Early America

Early American recipe books written for hearth cooking and baking included instructions for hoecakes, flapjacks, waffles, and pancakes made from cornmeal, wheat, and other locally available flours. These simple breads were “baked” in covered iron pots or fried in skillets or griddles. When early American recipes describe “baking” breads and cakes – the home cook knew to place the dough or batter in a Dutch oven with hot coals underneath and on the lid.

Puddings were another hearth-prepared option. The batters for puddings were placed in fabric pudding bags or pudding cloths, tied at the top, and put in boiling water or hung over a pot of boiling water to steam. English and early American cookbooks include many versions of sweet or savory puddings. Puddings were heavy, dense, and calorie-rich and usually included grain (flour, cornmeal, oats), dried fruits, and fat (animal fat, butter, eggs or all three). Today, many are familiar with holiday fruitcake or Scottish haggis, both adaptions of early puddings cooked at a hearth.

Making Bread and Cake Rise in Early America

Saleratus, a leavening agent and early form of baking soda, is often called for in bread or cake recipes in the early 1800s. However, its quality varied, making it difficult to judge how much was needed. Too little and the cake or bread didn’t rise; too much gave baked goods a bitter taste. Name-brand commercially produced baking powder such as Royal and Rumford baking powers weren’t sold until the late 1800s.

Recipes requiring yeast were more challenging because commercially packaged yeast was not sold until the late 1800s. Home bakers had to purchase brewer’s yeast from a local beer brewer or make their own yeast. Mary Randolph provided the following recipe in The Virginia Housewife (1836).

Patent Yeast

Put half a pound of fresh hops into a gallon of water, and boil it away to two quarts; then strain it, make it a thin batter with flour; add half a pint good yeast, and when well fermented, pour it in a bowl, and work in as much corn meal as will make it the consistency of biscuit dough; set it to rise, and when quite light, make it into little cakes, which must be dried in the shade, turning them very frequently; keep them securely from damp and dust. Persons who live in town, and can procure brewer’s yeast, will save trouble by using it: take one quart of it, add a quart of water, and proceed as before directed. p. 137

Hearth Baking a Cake in the 21st Century

The challenges of baking on a hearth became very real to me when I tried it for the first time at the historic Farmington Historic Home in Louisville, Kentucky. I chose to prepare Lettice Bryan’s Washington’s Cake from her 1841 cookbook, The Kentucky Housewife.

Replacing saleratus, which is not easily available, was my first challenge. Either baking soda or baking powder could have been used; I chose baking powder. Since baking powder did not need to be dissolved in hot water, I skipped the first step in the recipe and added the baking soda to the flour.

I needed “three gills of buttermilk.” What is a gill? A gill equals 4-5 ounces and was a traditional English measurement for liquids and was sometimes the same as a “teacup” in old recipes. I guessed and used 12 ounces of buttermilk or 1 ½ cups in modern terms. Standardized measuring cups were not adopted until the late 1800s.

Creaming one pound of butter (4 modern sticks) and a “pound of powdered sugar” was the real challenge. The “powdered sugar” referenced in the recipe is not the same as modern confectioner sugar. In early America, sugar was purchased in solid chunks, usually cone-shaped. Home cooks had to grate off the amount of sugar needed and pound it to achieve the fine-grained sugar we buy in bags from the grocery store. A pound of modern granulated sugar equals approximately 2 ½ cups. It took at least 30 minutes to “beat to a cream” the butter and sugar by hand using a heavy wooden spoon. And then the 6 eggs needed to be beaten well. By this point, my arm was getting really tired.

I didn’t have whole nutmegs and wasn’t sure how much powdered nutmeg to use. I used about 2 teaspoons. How did I decide? I tasted the batter. How much white wine is “a glass?” I guessed and used about ¾ cup. How many cups of flour equal 18 ounces? I googled the answer and added 4 or 5 cups.

I adapted the last steps. I mixed the liquids (buttermilk, eggs, and white wine) and added them alternatively with the flour, baking poweder,and nutmeg. Another 15 minutes of beating with a wooden spoon to get a “very smooth” batter!

The final step required putting the batter in a buttered square baking pan inside a large Dutch oven with a lid. I didn’t have a square baking pan that would fit in the Dutch oven, so I buttered the Dutch oven and baked the cake in it. Note that Mrs. Bryan recommends a “moderate” oven but does not say how long! Cast iron Dutch ovens don’t have thermometers anyway – so more guessing. I put the Dutch oven on a gridiron with hot coals underneath and on top the lid, making sure to rotate it every 10-15 minutes so the side nearest the fire would not overcook. After about 45 minutes, I guessed it was done.

And a miracle occurred!!! My first hearth-baked cake was fully baked but not burned, although one side browned more than the other and one edge stuck to the pan. And it was delicious; very much like a modern pound cake.

What did I learn from my experiment? I’m even more thankful for the products of the Industrial Revolution – electric mixers, electric ovens with thermometers, prepackaged and standardized ingredients, and standardized measuring cups and spoons. Pre-industrial baking also confirmed something I already knew – throughout history women had lifetimes of specialized skills and knowledge that was not written down and has been mostly unrecognized, dismissed, and forgotten.

To learn more . . .

For more about the history of daily life, primary sources, and instructional activities by this author:

- Visit Farmington Historic Home in Louisville, Kentucky

- Blog Post: Mrs. Bryan’s “Kentucky Housewife”: Managing a Household in the 1830s

- Discovering Quacks, Utopias, and Cemeteries;

- Exploring Vacation and Etiquette Themes in Social Studies

- Investigating Family, Food, and Housing Themes in Social Studies

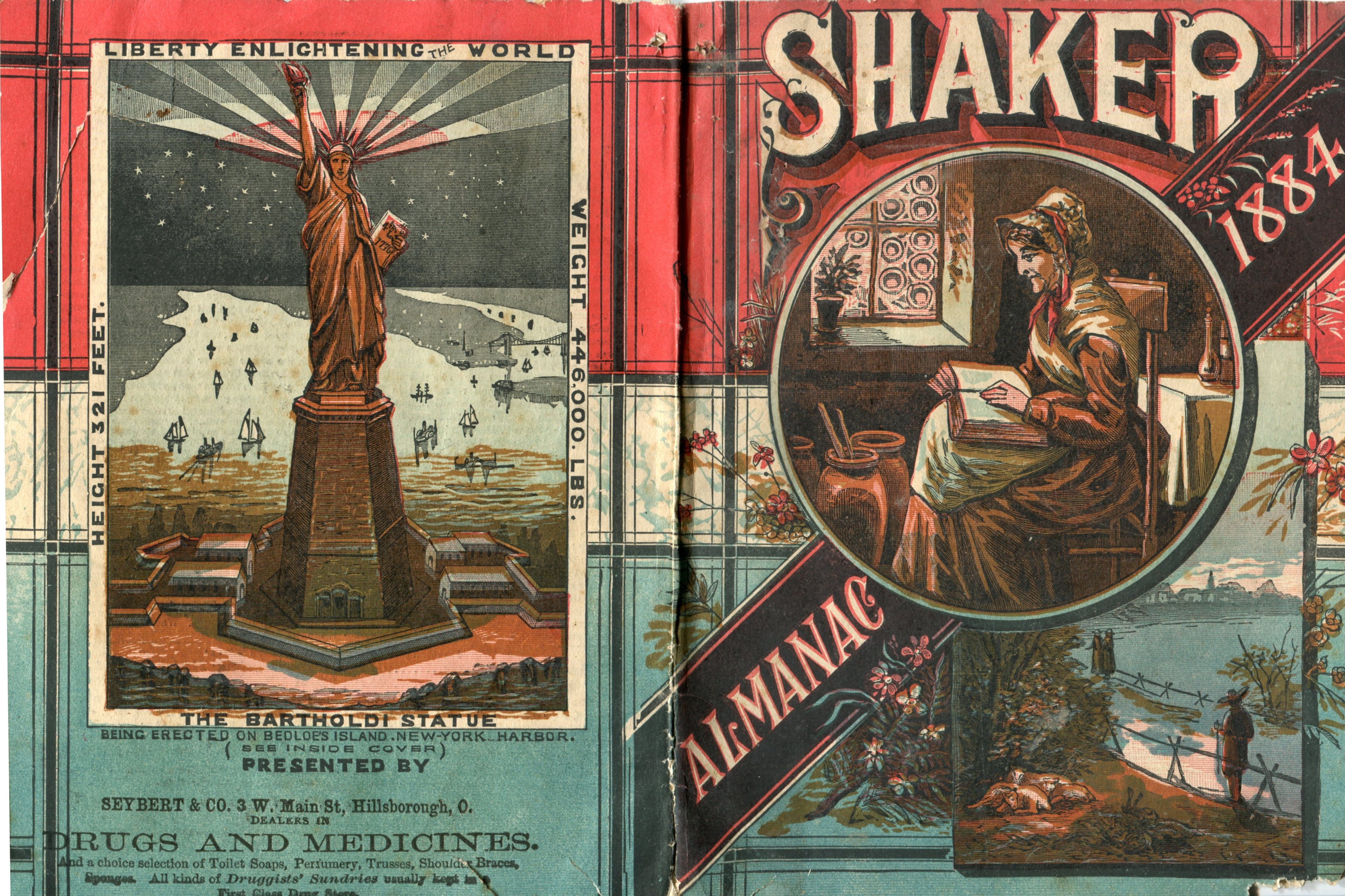

Heading Image: Woman Baking Pancakes (c. 1790 – c.1810) by Adriaan de Lelie