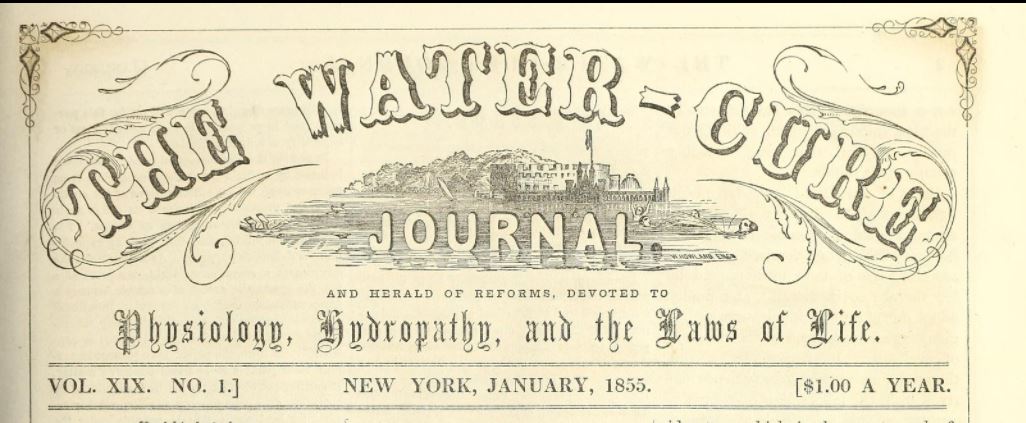

Hydropathy, or the water cure, was a 19th-century health reform movement and treatment popular in Europe and the United States. Patients soaked in cold or hot baths, took showers, were wrapped in wet compresses, sheets, belts, or special wet dresses, and also drank vast amounts of water. Hydropathy became a popular craze – a treatment for existing medical problems, a preventative for future problems, and a holistic lifestyle.

Select the images for a larger view and more information.

What is pseudoscience?

Hydropathy was pseudoscience, a treatment appearing to be scientific but not proven effective or safe using scientific research. Did its 19-century practitioners, promoters, and patients know the claims for hydropathy were not proven? Some did but these quacks promoted it anyway for their own financial gain. Many others genuinely believed in hydropathy’s benefits in an era when modern scientific methods were still developing. Furthermore, its incredible popularity was a stamp of authenticity for many of its followers.

The curative power of water was recognized by the ancient Greeks and Romans. Mineral springs were popular for centuries before the hydropathy craze. For example, in 18th century Bath, England, visitors to the Pump Room drank mineral water from the nearby hot spring. This “watering place” was located on the ruins of ancient Roman baths. In America, the wealthy vacationed at mineral spring resorts such as White Sulphur Springs, Virginia (now The Greenbriar in West Virginia) and Saratoga Springs, New York, and dozens of smaller, local springs for both their health and entertainment.

However, the atmosphere at hydropathy treatment centers was very different than previous well-known mineral spring spas. Popular mineral spring spas were associated with entertainment and indulgence more than health. Visitors socialized, danced, flirted, indulged in fancy food and alcohol, and gambled. Residential hydropathy centers focused on sobriety, strict diets, exercise, and water in all forms.

Hydropathy as 19th Century Alternative Medicine

The nineteenth-century hydropathy fad began when a European peasant, Vincenz Priessnitz (1799-1851), treated animals and himself through cold water applications and sweating and reported his methods cured gout and rheumatism. In just a few years, Priessnitz had hundreds of patients. Physicians and other medical practitioners and patients across Europe and the United States adopted and adapted the water cure. Hydropathy was one of many approaches to medicine and health offering alternatives to the treatments of regular physicians. Promoters of vegetarianism, abstinence from alcohol or tobacco, botanical cures, phrenology, homeopathy, and Mesmerism often combined their approaches in comprehensive guides to health.

Hydropathy and other holistic healing systems focused on more than just curing existing ailments. This movement tapped into contemporary trends focusing on a healthy lifestyle. Healthful living was viewed as a moral imperative; unhealthful living was viewed as sinful in the evangelical reform climate of the era. Hydropathy regimes include prescriptions for fresh air, exercise, special diets, and the elimination of various habits negatively associated with a fast-paced, urban lifestyle. The recommendations were similar to those promoted by contemporary health reformer Sylvester Graham (1794-1851) – a vegetarian diet, no rich food or “stimulating” beverages containing alcohol or caffeine, and restrictions on sexual activity.

Everybody’s Doing It!

The first American establishments opened in New York City, and 1860 in 1943. In the next twenty years, at least 27 hydropathic treatment centers opened, two medical schools of hydropathy were established, several water cure journals were published, and over one hundred male and female practitioners provided therapy in the United States. The water cure regime could be followed at home with the help of water cure practitioners and advice publications. Those who could afford the expense visited water cure spas offering treatments in scenic settings, educational classes and lectures, amusements, and interaction with other patients.

Testimonials from well-known authors and reformers increased the popularity of the treatments. Lucy Stone, Amelia Bloomer, Susan Anthony, Horace Greeley, and William Alcott praised hydropathy. Harriet Beecher Stowe spent almost a year at one of the most expensive and exclusive water cure spas located in Brattleboro, Vermont. Charles Darwin was treated for three months as a resident at the Malvern residential facility in England and had an outdoor shower and bath installed at his home to continue the treatment.

Alfred Tennyson promoted the hydropathic cure in 1844 when he described his treatment at a hydropathy center in England in a letter (Feb. 2, 1844). “Much poison has come out of me, which no physic (reference to medicine that purges; cathartic; laxative) ever would have brought to light. . . I have been here already upwards of two months. Of all the uncomfortable ways of living . . . hydropathical is the worst; no reading by candlelight, no going near fire, no tea, no coffee, perpetual wet sheet in cold baths and alternation from hot to cold: however have much faith in it.”

Charles Darwin and Alfred Tennyson continued to have poor health for much of their lives but both believed the water cure relieved their worst symptoms.

Miracle Cures for Women

The water cure movement was especially promoted by and for women. Many rejected the methods of regular physicians for treating female disorders and childbirth. Caroline Smedley, the author of Ladies’ Manual of Practical Hydropathy (first published in 1861), was active in the day-to-day running of the treatment facilities run by her and her husband. She took responsibility for the female patients and trained female bath attendants who later went on to become practitioners themselves.

Hydropathy proponents also challenged contemporary beliefs that women should avoid strenuous exercise and wear tight corsets and voluminous skirts. Between 1850 and 1852, the Water Cure Journal called for less restrictive clothing for women and even asked readers to submit ideas. Most were similar to outfits worn by the women of the utopian Oneida Community and popularized by women’s rights activist Amelia Bloomer.

Critics of Hydropathy

Despite its popularity, hydropathy was not praised by everyone. Critics reported deaths due to improper treatment, questioned its effectiveness, and accused hydropaths of being quacks. The hydropathy craze reached its zenith in the mid-1850s, but it did not disappear. Its concepts of cleanliness, exercise, and diet continued to be prominent in other pseudoscientific approaches and legitimate efforts at hygienic reform.

Popularity Does Not Equal Effectiveness

Today, treatments involving water are labeled as hydrotherapy and these methods continue to be a part of many systems of “natural” medicine. Modern water therapy, aquatic therapy, pool therapy, balneotherapy, cold water baths, and other uses of water in various forms and temperatures can have an effect on different parts of the body. However, a lack of scientific studies exists and the effectiveness of many of these approaches is questionable. Popularity still doesn’t make a pseudoscientific cure safe or effective.

To learn more about the history of medicine, disease, and quackery:

-

Discovering Quacks, Utopias, and Cemeteries, Modern Lessons from Historical Themes

Discovering Quacks, Utopias, and Cemeteries, Modern Lessons from Historical Themes- Blog Post: What is scrofula? Can it be cured?

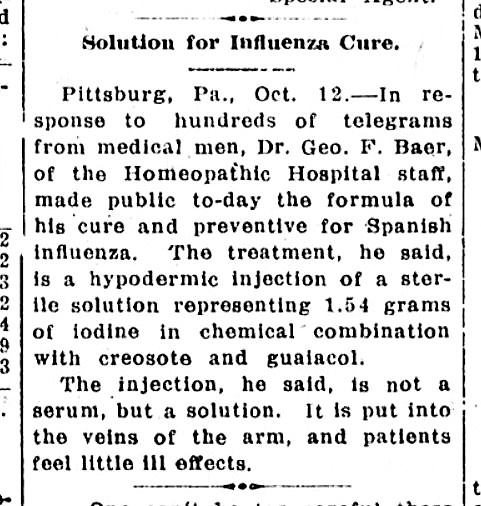

- Blog post: Cure for the Flu!? Don’t fall for quack cures.

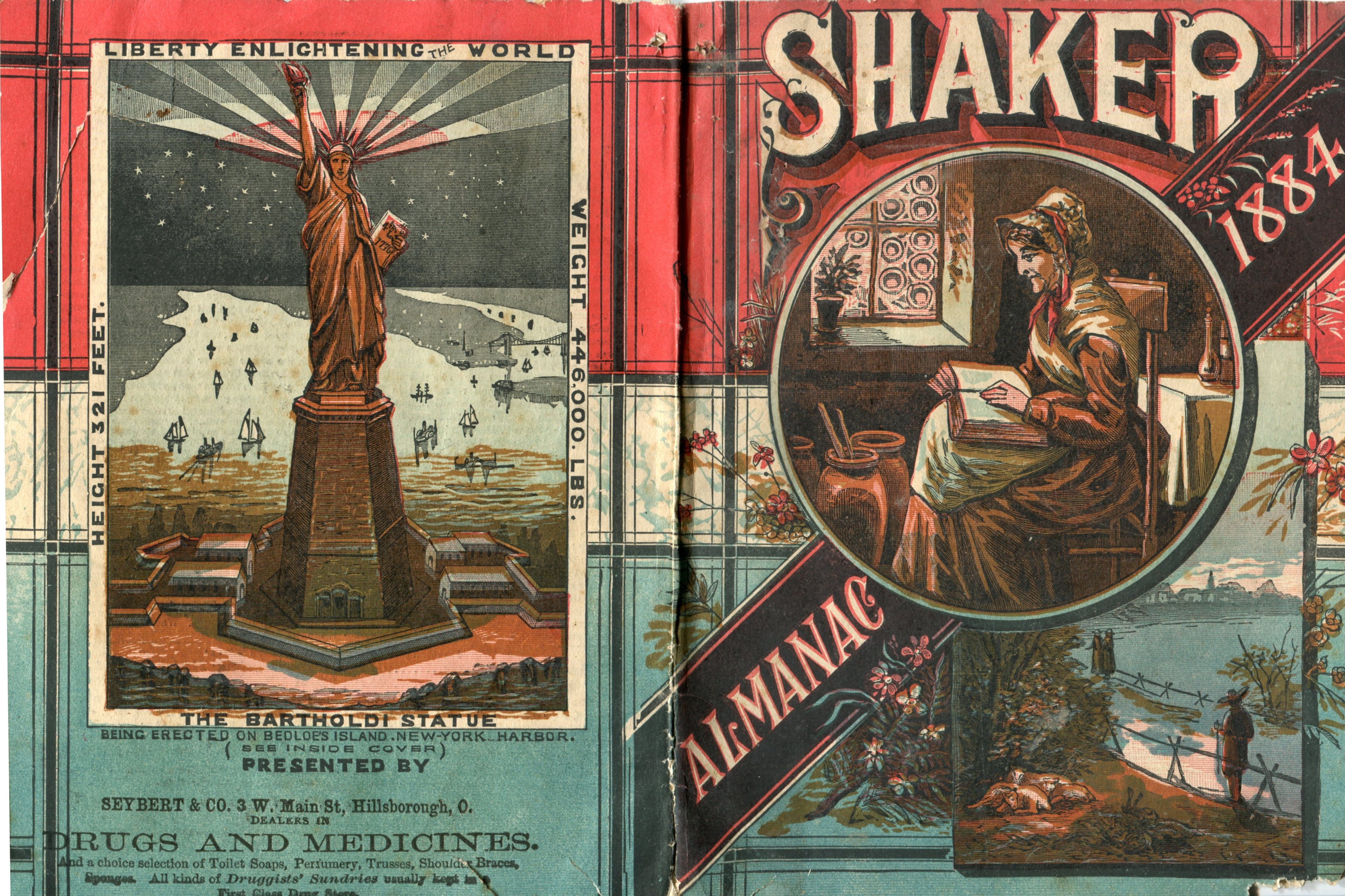

- Blog post: Almanacs: Information before the Internet

- Blog post: Caveat Emptor and Cui Bono: Ancient Advice for Modern Consumers

- More books by this author

References:

- Discovering Quacks, Utopias, and Cemeteries: Modern Lessons from Historical Themes

- “A Brief History of Psychiatric Hydrotherapy,” in The Institute for the History of Psychiatry: The Annual Report to the Friends, 2005-2006, p. 15

- Hilary Marland and Jane Adams, “Hydropathy at Home: The Water Cure and Domestic Healing in Mid-Nineteenth-Century Britain,” in Bulletin of the History of Medicine, Fall 2009.

Discovering Quacks, Utopias, and Cemeteries, Modern Lessons from Historical Themes

Discovering Quacks, Utopias, and Cemeteries, Modern Lessons from Historical Themes