Crafts, sewing, and needlework projects are growing in popularity as people spend more time at home. Etsy, the online marketplace for arts and crafts supplies and finished work, boomed in 2020. However, getting creative at home for fun or profit is not a new thing. In the 19th century, creative projects called “fancywork” were all the rage.

Less plain needlework and more fancywork

Since the dawn of time, women were spinning, weaving, sewing, and mending clothing and fabric. These tasks were never-ending. Only the wealthiest women had time for decorative or creative needlework. However, in the late 18th century, the process to make fabric was mechanized and industrialized. Women started discarding the spinning wheel and loom in favor of factory-produced textiles. The home sewing machine was introduced in the 1850s and became affordable for average households by the 1860s through installment plans. More and more women were freed from “plain sewing” for daily household needs and pursued more creative projects called “fancywork.”

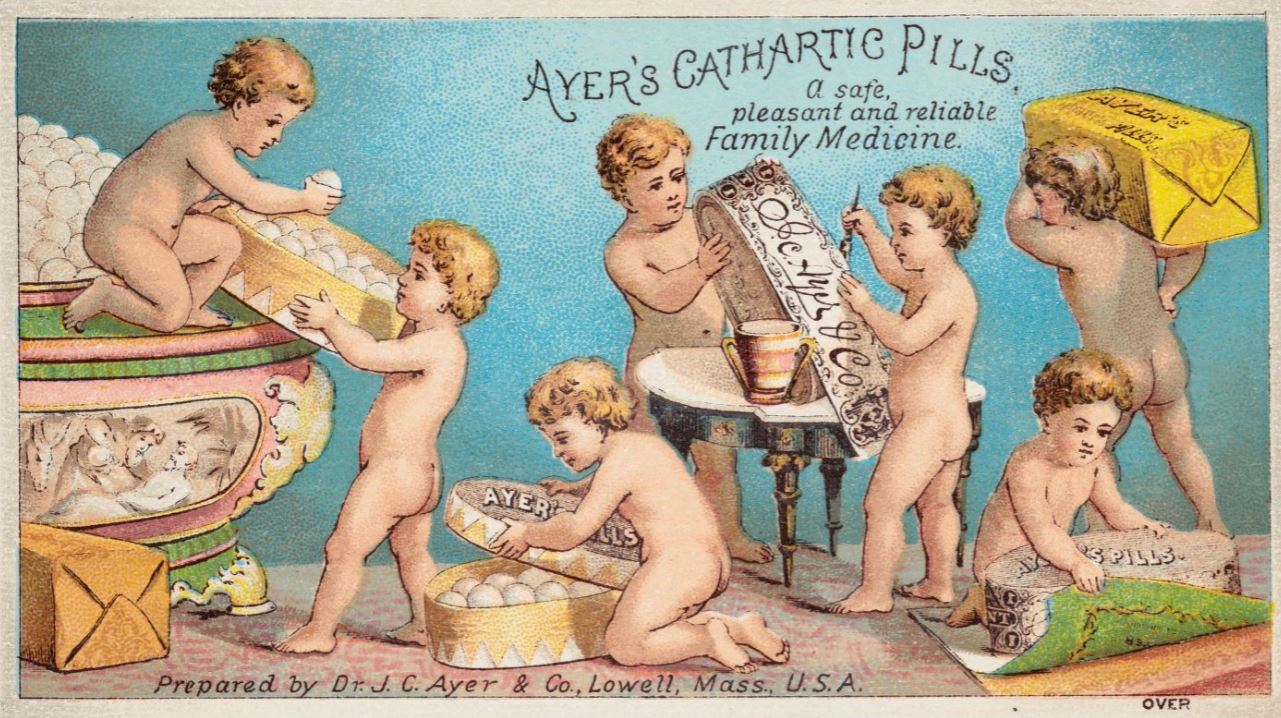

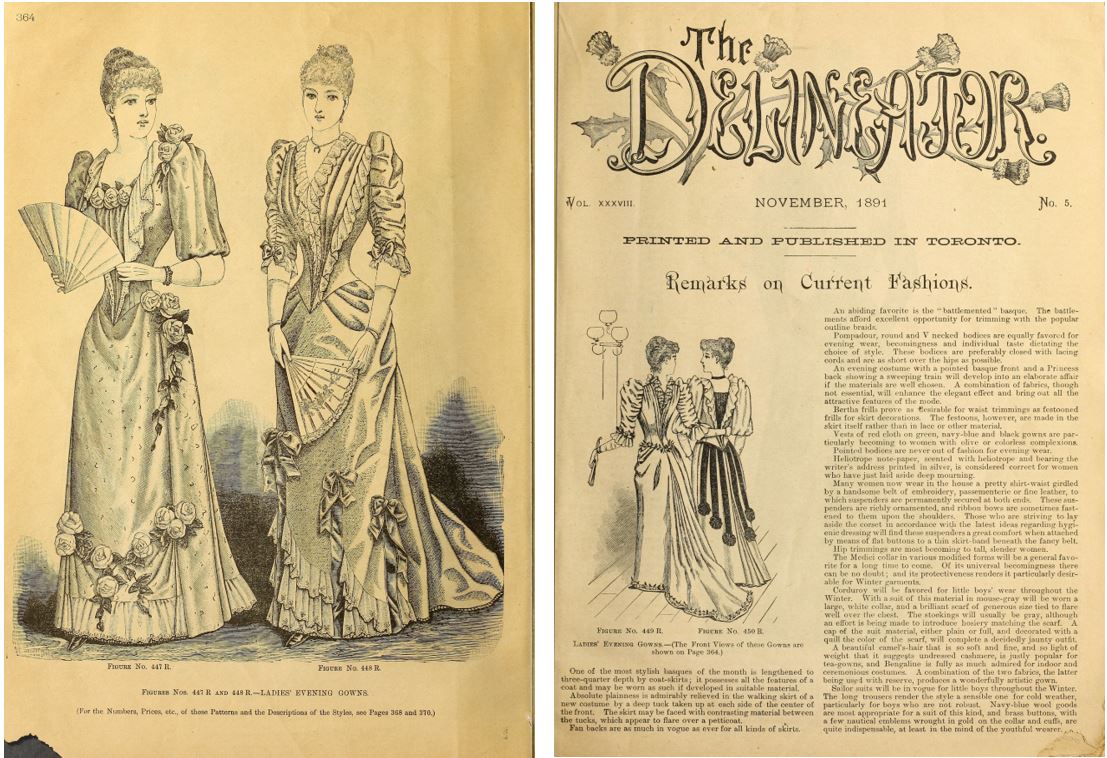

At the height of its popularity from the 1840s to the 1880s, the fancywork craze was about hand-crafting decorative items for the home or for gifts. However, it was made possible by the Industrial Revolution. Mass-produced sewing and craft supplies (fabric, ribbon, wools for embroidery, beads, punch paper cardboard, patterns, and more) were readily available and less expensive. Growing railroad networks helped supplies reach formerly remote small towns. The federal postal service made ordering supplies in the mail easy and reliable. Industrialized printing was cheaper so more and more books, newspapers, and women’s magazines were published, full of ideas for creative projects.

Fancywork also represented middle-class cultural ideals. Beautiful homes were considered morally uplifting for the whole family. Decorating a home with homemade creations saved money, displayed a woman’s thriftiness and creativity, and created a pleasant environment for the whole family – the 19th-century middle-class family ideal.

19th century fancywork techniques and projects

Some of the 19th-century fancywork is recognizable today and continues to be pursued and promoted on 21st-century digital publications like Pinterest, Etsy, and Instagram. Items to wear or decorate the home were created using techniques still familiar in the 21st century – sewing, crocheting, knitting, embroidery, and patchwork or appliqué quilting.

A new simplified form of ornamental needlework was especially popular – Berlin work or canvas work. Today, we call it needlepoint. Berlin needlework on commercially produced canvas or perforated cardboard with wool yarns first appeared in Europe in 1805. The patterns, printed on a grid, were easy to follow and the basic stitch was simple, requiring less skill than many previous forms of embroidery. Completed Berlin work was fashioned into bags, pictures, rugs, footstools, chair coverings, fire screens, slippers, and all sorts of three-dimensional creations. Read more about Berlin work mottoes here.

Other 19th-century fancywork projects are not common today – hair work (creating wreaths and other items from human hair), bobbin work, braiding, netting, and creating laces and velvet balls (pom-poms). Nineteenth-century women expanded from needlework projects to new three-dimensional creations using wire, beads, natural materials, feathers, hair, and recycled materials. Wirework referred to using wire and beads to create decorative baskets or vases. Potichomania, applying paint or paper images to glass vessels to give them the appearance of painted porcelain, was also popular.

Women created and decorated accessories such as bags, purses, ornamental hair combs, aprons, scarves, handkerchiefs, and glove cases. They created gifts for the men in their lives such as smoking caps, slippers, watch holders, and hair watch chains. Household organizers made from cloth, cardboard, wood and other materials were created and/or decorated for hair combings (saved for hair work projects), brushes, newspapers, sewing boxes, and letter writing materials. Homemade workbags, needlebooks, pincushions, inkstand mats, letter racks, and pen wipers were also popular. Decorative doilies, table covers, dresser scarves, bed coverings, and covers for chair arms and backs were stitched and decorated. Three-dimensional wreaths or bouquets of flowers made from shells, wax, wool, or hair were hung on the walls or mounted under glass domes.

Fancywork for profit as well as pleasure

Just like today, 19th-century fancywork was pursued for creative pleasure. Completed projects were displayed in the home or presented as handmade gifts. But completed fancywork items and instructions were also produced by women for profit.

Charity bazaars or fundraising fairs were common between the 1830s and early 20th century. Women created fancywork for sale to raise money for abolition, suffrage, churches, mission societies, and many other charitable organizations and causes. Entire sections of fancywork instructional manuals were dedicated to items to make for resale. During the Civil War, thousands of dollars were raised at “sanitary fairs’ dedicated to raising funds for the United States Sanitary Commission that sought to improve conditions in military hospitals. The novel Gone with the Wind, features a widowed Scarlett O’Hara at a Confederate charity bazaar during the Civil War.

Individual women earned their living by producing fancywork for sale. For example, in Jane Austen’s novel Persuasion, Mrs. Smith produces fancywork articles for sale including “little thread-cases, pin-cushions and card-racks.” (Chapter 17 of Persuasion) Shaker women produced fancywork items for sale to support their communal villages in New England, Ohio, and Kentucky. Sewing baskets and boxes, pin and needle cushions, feather fans and dusters, dolls, and other small, personal items were sold as well as the better-known Shaker seeds, brooms, and furniture.

Matilda Marian Pullan (1819-1862) made a living by providing lessons in fancywork and needlework, designing patterns, selling supplies, and publishing instructional articles and books. She published several books on needlework and sewing. Her Lady’s Manual of Fancy-Work, published in 1859, was an encyclopedia of the art with nearly 250 pages and over 300 illustrations.

In the introduction to her book, Ms. Pullan noted that even though the Atlantic telegraph was a wonderful invention, it couldn’t compare with the sewing machine.

“The SEWING MACHINE . . . with a promise of social immunities, of domestic joys, the full results of which pen of woman, or even tongue of Angel could hardly describe. . . . We hail with joy that great Liberator of our sex, the Family Sewing Machine.” (p. xiv, The Lady’s Manual of Fancy-Work)

Esty and the fancywork revival

The Industrial Revolution and the invention of the sewing machine allowed women to abandon much of the “plain” needlework. Mass production, commercialization, and advertising and sales of the needlework and craft supplies drove the 19th-century fancywork trend. Over one hundred years later, computerized sewing and embroidery machines, the internet, social media, and online sales platforms like Etsy are driving new fancywork trends. Sewing machines sales are booming this year. And millennial “sewists” are seeking new outlets for creativity.

Fancywork expert Matilda Marian Pullan would have loved Etsy. She said “fancy Needlework is not only a pleasant and ever varying resource against ennui, but a direct agent in the cultivation of home pleasures and home affections.” (p. xiii, The Lady’s Manual of Fancy-Work)

Test your knowledge of 19th-century needlework with this fun quiz – Fancy Work: Needlework of the 1800s Quiz

References:

- Nancy Dunlap Bercaw, “Solid Objects/Mutable Meanings: Fancywork and the Construction of Bourgeois Culture, 1840-1880,” Winterthur Portfolio, Vol. 26, No. 4 (Winter, 1991), pp. 231-247.

- Beverly Gordon, “Victorian Fancywork in the American Home: Fantasy and Accommodation,” in Making the American Middle-Class Woman & Domestic Material Culture, 1840 – 1940, pp. 48 – 68.

- Marianne Van Remoortel, “Threads of Life: Matilda Marian Pullan (1819-1862), Needlework Instruction, and the Periodical Press,” Victorian Periodicals Review, Vol. 45, No. 3 (Fall 2012), pp. 253-276.

Read more about the history of daily life in my books:

Author’s note:

My grandmothers influenced my love of “fancywork” by teaching me to sew, quilt, embroider, and crochet. I inherited my mother’s love of collecting fabric, project supplies, and “rescuing” unwanted needlework from yard sales and thrift shops. My special weakness is crewel embroidery and here are a few photos of projects I have completed or rescued. I call my collection my “Museum of Average Women.” Let’s just say that Etsy and Ebay have added to my collection in recent months . . . . .

Investigating Family, Food, and Housing Themes in Social Studies

Investigating Family, Food, and Housing Themes in Social Studies

Love this article!! Congratulations on the book!!