Decorating with inspirational phrases, quotes, or single words is fashionable. Vinyl stickers of popular words and phrases are created using cutting machines and pasted on everything. Do-it-yourself ideas for embellishing walls, pillows, plaques, and even laptops with personal mottoes can be found online and in print. Home stores sell decorative items with stock phrases for those without the time or skills to make their own.

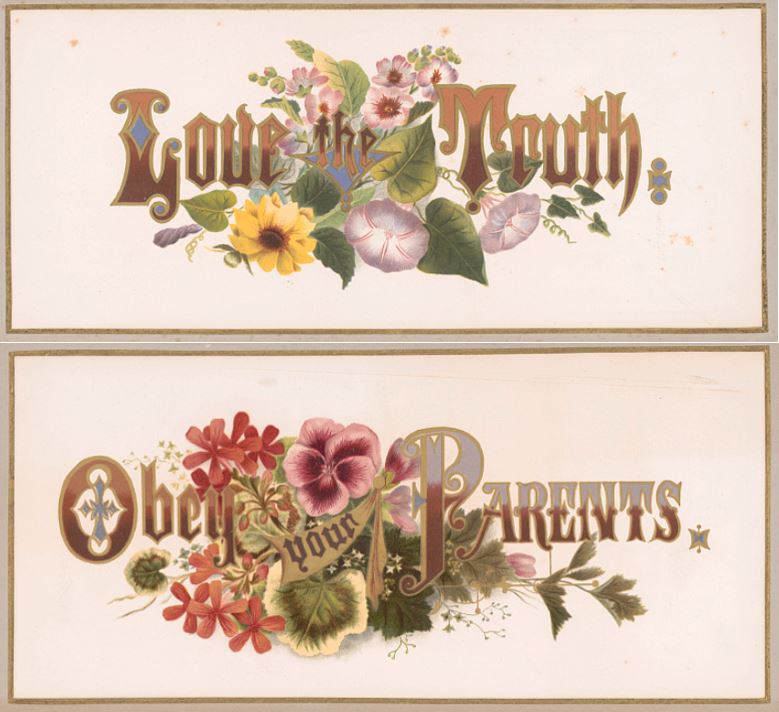

Decorating with mottoes, short sentences or phrases communicating a rule or philosophy of a person, family, or institution, is not a new thing. For centuries, mottoes appeared on coat-of-arms, flags, banners, and grand buildings. In the late 19th century, handmade and commercially produced mottoes became especially popular in homes. Most conveyed Christian messages, reflecting the prominence of evangelical Christianity in the “cult of domesticity” prominent in middle-class culture of the era.

Select the images for a larger view and more information.

Women, religion, and home in the 19th century

The cult of domesticity (also called the cult of true womanhood) was a prominent theme in middle-class American and British culture beginning around 1820. Women were judged by their religious piety, sexual purity, submissiveness to a husband, attentiveness to children, and domestic accomplishments in the home. Women were expected to compassionate and their primary duty was home, husband, and children. Considered unsuited for the aggressive and sinful world outside the home, women were restricted from public roles in government and were not allowed to enter professions dominated by males. Outside the home, middle and upper-class women were limited to working with charitable efforts and religious and reform movements because these roles were compatible with their perceived feminine personalities and abilities.

On the other hand, men were to display the masculine traits of rationality, power, domination, and drive to earn wages away from home. While men and women were supposed to live in separate spheres of influence, in marriage, the two opposites, men and women, were believed to be a perfect and complementary whole.

Nineteenth-century essays, sermons, novels, poems, and manuals communicated this connection between home, family, religion, and women. Numerous domestic advice books and magazine articles described the ideal home and how a woman should create it through cooking, cleaning, decorating, raising children, managing servants, and every aspect of proper household management. It was in the homes of a growing middle class that decorative mottoes were prominently displayed, linking religion, home, and roles and responsibilities of 19th-century women.

Printed & needlework mottoes for the home

Printed “chromo” mottoes and frames were widely available for sale and the most popular size was 8 ½ by 21 inches. Women could also demonstrate their skills at needlework by embroidering decorative mottoes. By the 1870s, embroidered mottoes on perforated cardboard were extremely popular and featured on the walls of homes across America and Britain.

Perforated cardboard was introduced in the late 1700s to use as the background for needlework projects. This thin, manufactured cardboard with pre-punched holes was cheaper and easier to use than traditional fabric backgrounds. It could be used to create pictures, mottoes, bookmarks, and three-dimensional boxes, baskets, purses, and other decorative objects.

By the 1840s, needlework manuals and women’s magazines such as Godey’s Lady’s Book were carrying instructions for perforated cardboard projects. Needlework and craft supply businesses advertised perforated cardboard pre-printed with popular mottoes ready for women to personalize with their choice of threads, colors, and stitches. The past-time was so popular that it was referenced in several novels in the 1850s and 1860s.

The following is from an 1877 guide to needlework:

“Never in the history of fancy work has there been a fashion more marked and popular than the present rage for every description of work upon perforated card. The varieties of articles are constantly increasing, and for the time, at least, this material and work has largely superseded all others.

The material is stiff card, pierced with minute holes at regular intervals, some of it being fine enough to require the finest cambric needed for working, while others are coarse enough to require double Berlin wool or chenille to fill the space. It can be obtained in large sheets or in cards cut for any purpose required, with ornamented borders. It is made in many colors, and in gold-faced and silver-faced sheets.

The stitch for working is usually the cross-stitch of canvas work, but straight or diagonal lines are often used to fill up spaces where the cross-stitch would narrow or widen the pattern too much. (p. 120, The Ladies’ Guide to Needle work, Embroidery, Etc.: Being a Complete Guide to all Kinds of Ladies’ Fancy Work by S. Annie Frost, 1877)

The most popular motto was “God Bless Our Home”; around 60% of the mottoes of the era carried an explicitly Christian message. Patriotic themes and nostalgic references to home or family members were also popular. Some mottoes were associated with the temperance movement or with fraternal organizations such as the Masons or Odd Fellows.

These prominently displayed mottoes reflected the ideals of a family and a wider 19th-century culture. They also demonstrated changing technology. In the late 19th century, chromolithography was a new technique for replicating original paintings for mass production and sale. Perforated cardboard and pre-printed needlework designs were also mass-produced consumer goods sold to a growing middle-class market. Would these mottoes have been as popular without their mass production and sale?

What does decorating with words really mean?

Consider the words and mottoes on 21st-century walls and decorative items. Do these ornamental words really reflect the values of an individual or that person’s fashion taste and style? Taken as a whole, do modern ornamental mottoes convey the values of modern American society, or is decorating with words just a popular and inexpensive decorating trend? Can it be both?

Test your knowledge of 19th-century needlework with this fun quiz – Fancy Work: Needlework of the 1800s Quiz

To learn more about historical home and family:

- Investigating Family, Food, and Housing Themes in Social Studies

- Blog Posts:

- More books by this author

References

- “Perforated Cardboards: A Support for Embroidery Used for Various Everyday Objects in the Victorian Age” by António João Cruz*, Luciana Barros and Leonor Loureir in Restaurator. International Journal for the Preservation of Library and Archival Material, March 2019, pages 35–67.

- Chapter 3: Words to Live By in Death in the Dining Room & Other Tales of Victorian Culture by Kenneth L. Ames.

One thought on “Decorating with Mottoes: Inspirational Words in 19th Century Homes”