What’s a shoat? Before the Civil War, cookbooks included dozens of recipes for shoat. Today, this word for pork only appears glossaries for journalists covering agriculture. A shoat (also spelled shote) is a young pig under one year old. Antique words and old recipes, like antique tools or technology, illustrate changes in daily life. Weird old words and old practices can grab students’ attention and connect to wider economic, political, and social themes.

It’s Cold Enough to Kill Hogs

In 1800, over 80% of the American labor force worked in agriculture. Over the 19th century, technological and industrial change enabled fewer people to grow the nation’s food supply. As more and more people migrated to urban areas, food became something purchased in packages, not raised on the family farm. The 1920 census marked the first time when over 50% of the U.S. population was defined as urban. Today, only 19% of America’s population live in rural areas; less than 2% of the labor force work agriculture.

Two hundred years ago, the food preparation knowledge and skills of average Americans was completely different than today. Americans knew fresh pork had to be consumed quickly or the meat would spoil. They knew cold weather and large quantities of salt were needed to butcher hogs and preserve the meat.

Today, butchering animals seems shocking; the details are obscured in slaughterhouse factories. For most of history, butchering was a part of everyday life. In cold weather, the pig was killed and the blood drained from the carcass. The skin scalded with boiling water so the bristles, or hair, could be easily scraped from the skin. Internal organs were removed and most were used. The bladder was rinsed and used to cover stoneware jars or lard; the intestines were cleaned used for sausage casings. The brains, heart, liver were consumed in various tasty dishes.

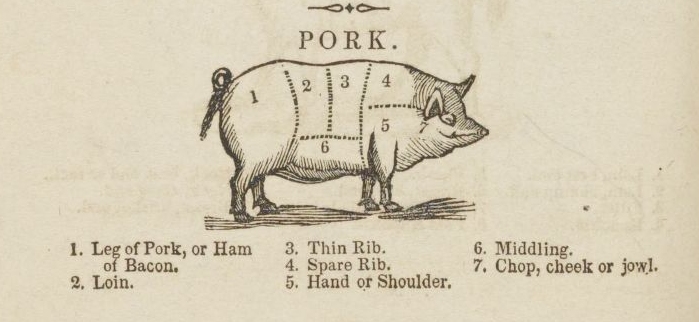

The carcass was allowed to cool before cutting into manageable pieces. All the bits were saved for sausage. Fat trimmings were made into lard. The fat was heated in large vats to render (liquefy) the lard for later use. Cracklings, the crisp fatty skin pieces remaining after the lard was rendered, were also used in cooking.

Large cuts such as hams, shoulders, or side meat were cured with mixtures of salt, sugar, spices and preservative (saltpeter or potassium nitrate). Smoking, hanging cured cuts of meats in an enclosed space with smoking fruit or nut woods, added additional flavor and protected the meat from insects.

Pork & Culture – The Staff of Life, or Not

Throughout American history, pork was especially popular in the American South. Travelers from northern states and Europe commented, positively and negatively, on the popularity of pork on southern tables of all social classes – from slaves to the wealthiest planters.

In the 1840s, Emily Burke, an Ohio writer visiting Georgia, commented that “the people of the South would not think they could subsist without their [swine] flesh; bacon, instead of bread, seems to be THEIR staff of life.”

Southern cookbooks from the 19th century, such as The Virginia Housewife (1824) by Mary Randolph and The Kentucky Housewife (1839) by Lettice Bryan contained dozens of recipes for pork, including many for the tender meat of young pigs, or shoats. Cookbooks from the same era by northern women, such as The American Frugal Housewife (1838) by Lydia Maria Child and Miss Beecher’s Domestic Receipt Book (1846) by Catharine Beecher also included many pork recipes, but didn’t use the word shoat.

Today, pork remains popular in the American diet, consumed second to beef for most of 20th century. In the 1990s, chicken became the second most popular meat. In the 21st century, pork sales as growing. Asian cuisines are trendy, especially Korean and Vietnamese pork dishes. Bacon is increasingly popular in everything– from appetizers to desserts. Most cooks in the 19th century would have known bacon came from the back (or loin) and the middling (or belly) cuts of the pig.

On the other hand, some cultures and religions, such as Islam, reject pork consumption completely.

Pork Barrels – The Pork Industry and Politics

While Lettice Bryan wrote recipes for hashed and corned shoat, shoat pie, and shoat steaks in the 1830s, the pork processing industry grew in urban centers such as Cincinnati, also known as “Porkopolis.” In the era before mechanical refrigeration, Cincinnati’s pork processing industry took place in the winter. After the Civil War, Chicago claimed the nation’s largest meat-packing industry. By the 1880s, mechanical refrigeration made it possible to slaughter and ship animals year around.

For centuries, pork barrels were used to store and ship salt-preserved meat. After the Civil War, as fewer Americans knew how to butcher a hog or preserve the meat, the term came to mean government spending by politicians to gain political support.

In the early 20th century, many Americans were re-acquainted with the process of butchering and preservation through Upton Sinclair’s expose on the abuses of the industry – The Jungle. Americans called for government intervention to insure food safety, a trend that continues one hundred years later.

Pork and Globalization

Pork is consumed and traded globally and one of the many agricultural products at the center of recent tariff battles.The United States, the European Union, and Canada export the most pork. Even though China raised the most pigs in 2018, they also imported the most pork.

Commodity reports for pork no longer quote prices for shoats; instead the prices of lean hogs are reported. Today, pork recipes call for pork loins or chops, not for shoat fore quarters, heads, or feet. The words we use tell a wide-ranging story of social, economic, political, and technological change.

To learn more . . .

For about the history of daily life and classroom ideas and activities, see Investigating Family, Food, and Housing Themes in Social Studies.

Thompson, Michael D. “”Everything but the Squeal”: Pork as Culture in Eastern North Carolina.” The North Carolina Historical Review 82, no. 4 (2005): 464-98. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23523182.

Pork is something that most students probably eat in their everyday life. Tying food into instruction is a great way to get students’ attention and make them interested in what you have to say. Teaching students about the history of the food they eat everyday integrated into social studies concepts will for sure get them intrigued. I’m going to ask students to take this quiz and provide them with samples of mincemeat (you can still get it in the baking section of most grocery stores) https://teachingwiththemes.com/index.php/mincement/ Can’t wait to use this information for a lesson!!

This information will be great in my middle school classroom when discussing different foods from different cultures and time periods. It helps to explain how families did all the work throughout most of history – from raising the animals, to butchering them, to cooking them.

“Pork Barrels – The Pork Industry and Politics” could be used to 8th grade social studies class when discussing how people were moving off the farms and into urban settings and how this caused people to have to find their meat sources since they were not raising their own meat in the cities.

The impact of globalization on our food sources is a great way to illustrate this trend to my 4th graders.