Cemetery and tombstone symbols have been reused and reinterpreted for thousands of years. The ancient Egyptians used pyramids, obelisks, sphinxes, and various symbols for monuments, temples, and tombs. Everything Egyptian became stylish again in the 19th century. During this Egyptian Revival, the designers of rural or garden cemeteries and families choosing tombstones and monuments adapted old styles to new tastes and trends. However, we can’t assume ancient architectural forms and symbols have the same meaning throughout time.

Select the images for a larger view and more information.

Iconography, the interpretation of meanings and uses of images, is an important element in the study of cemeteries and tombstones. In cemeteries, iconographers list and categorize decorative images and forms and seek to learn why those images were chosen, their meanings, and historical traditions. This search for answers is challenging because meaning changes over time, a reflection of shifting attitudes toward death, religion, family, and social class. Popular trends and individual tastes also influence tombstone and cemetery design.

Trend-setting ancient Egyptians

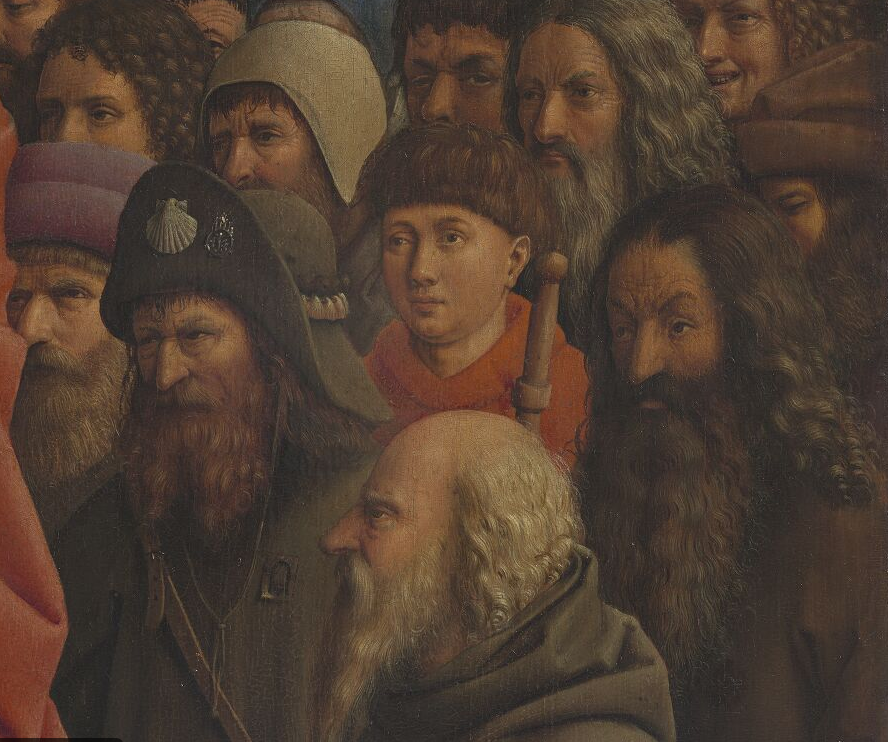

The ancient Egyptians are best known today for their impressive funeral monuments, rich tombs, and mummification. These customs, reserved for the rich and powerful in the ancient world, are well known today because the desert climate helped preserve its artifacts. Even in the ancient world, Egyptian architecture was admired and adapted by other cultures.

Ancient Egyptian monuments inspired the ancient Romans. Augustus Caesar commemorated his defeat of Cleopatra and Mark Anthony and the addition of Egypt to the Roman Empire by moving an Egyptian obelisk to the Circus Maximus in the city of Rome. It had been commissioned by Ramses II over one thousand years before Augustus and was one of seven Egyptian obelisks relocated to Rome.

The ancient Romans also adopted Egyptian styles for funeral monuments. The monument for the first century BC senator Gaius Cestius was a white marble-faced pyramid over 80 feet high. The surviving inscription noted the pyramid took 330 days to build. This ancient Roman monument, styled on an even more ancient Egyptian form, still stands today adjacent to a cemetery opened in the 18th century for non-Catholics.

Egyptomania: The 19th-century craze for everything Egyptian

In the 19th century, Egyptian Revival symbols and architectural styles became the hot new trend for cemetery gateways, monuments, and public memorials. Obelisk tombstones; pyramid mausoleums; flat-roofed mastabas; and wide, curved lotus-topped columns proliferated. Sphinxes, winged orb or sun-disks, and snakes were common motifs. Many of these originally pagan symbols were given new associations with Christianity through references to the biblical accounts of Hebrew enslavement in Egypt. Egyptian Revival symbols and architecture were also popular for prisons, factories, firehouses, railroad depots, bridges, theatres, schools, and even churches and synagogues.

Egyptomania was inspired by historical events of the era. Everything Egyptian became incredibly popular in Europe after the French (1798-1801) and British occupation (1882-1922) of Egypt. The Rosetta Stone, a stele with Greek and ancient hieroglyphic inscriptions discovered by the French invaders, provided the key for Francois Champollion’s translation of hieroglyphics in 1822. These events, along with the popularity of travel to Egypt promoted by published tourist guides and accounts of Egyptian tours, fueled the trend.

Ancient symbols are reused and reinterpreted over time and the meanings of those symbols are malleable. The Sphinx Monument, designed and donated by Jacob Bigelow and installed in Mt. Auburn Cemetery in Boston as a public monument in 1872, commemorated Union soldiers in the Civil War. Bigelow’s sphinx reinterpreted and blended Egyptian and American symbols.

Bigelow’s sphinx monument was widely misunderstood and misinterpreted during his lifetime and after his death, despite his efforts to explain the symbolism. Bigelow’s benevolent female sphinx was meant to symbolize a new nation. However, it was misinterpreted as the treacherous female sphinx of Greece myth who destroyed those who could not answer her riddles. 1 Ironically, the Egyptian Revival style was also used for a 90-foot granite pyramid erected in Richmond, Virginia’s Hollywood Cemetery in 1869 to commemorate the 18,000 Confederate soldiers buried nearby.

Essential/compelling question for the classroom:

How do symbols reflect the wider culture and traditions?

Display images of a pyramid, obelisk, uraeus, ouroboros (snake eating its tail), or winged sun and ask students to guess the meaning of each architectural form or symbol. Answers will be widely varied and most likely have little or no connection to their significance for an ancient Egyptian or 19th century American. However, student answers will reflect themes relevant to their own lives and the modern world.

Cemetery field trips often highlight historic preservation or the histories of well-known people from the local community. However, cemeteries and their monuments can illustrate a history far older than the surrounding community or its deceased. Ask your students to examine the common symbols and investigate the popularity and meaning behind these symbols. Decoding a symbol is never simple. Cemetery symbols reflect shifting attitudes toward death, religion, family, social class, popular culture, commercialization, and individual taste.

Test your knowledge

Test your knowledge of the symbols on tombstones with this short quiz.

To learn more about cemeteries, tombstones, symbols, and customs for commemorating the dead by Cynthia Resor, author of this post:

Discovering Quacks, Utopias, and Cemeteries, Modern Lessons from Historical Themes

About the header image: Louisville, Kentucky’s rural or garden cemetery, Cave Hill, was chartered in 1848. The Egyptian Revival Sphinx atop the Peaslee family monument was installed in the early 20th century.

The inscription on the base of the monument: Ella Harper Harbeson Peaslee, January 20, 1903, Eleanora Harbeson Peaslee, March 5, 1904; Charles Rowland Peaslee, November 24, 1905.

I love Egyptian history!!