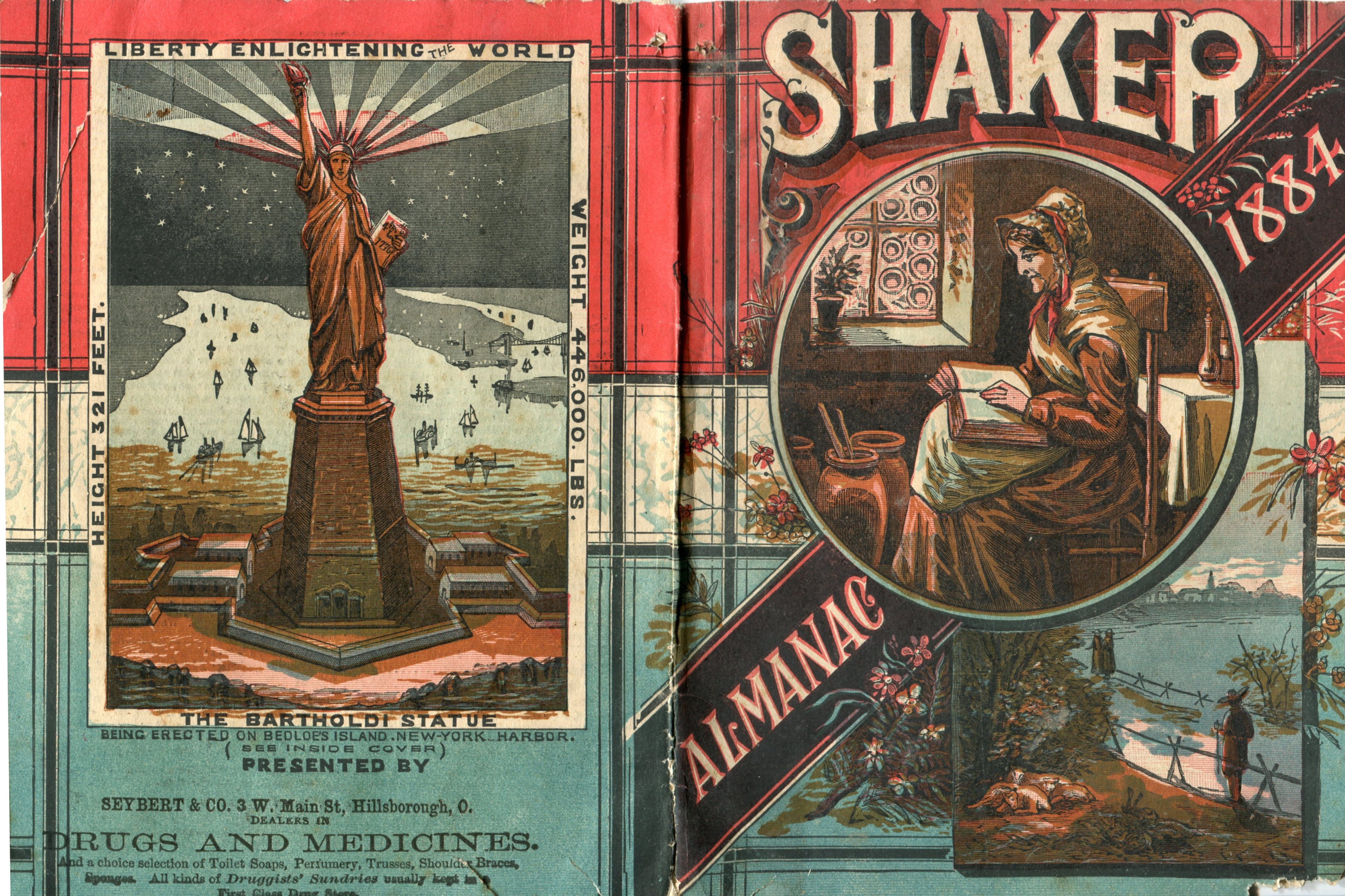

Almanacs were a popular and handy reference for information and entertainment centuries before internet search engines, calendar apps, YouTube, blogs, and Google Maps. And like the internet, almanacs also informed us about new products and services through advertising and promotional articles.

Select the images for a larger view and more information.

At the heart of all early almanacs was a calendar. Almanacs first appeared in the ancient and medieval world, long before printing, to communicate important dates and information related to astrological predictions, events and heavenly influences on health or religious observances and their importance. Throughout time, almanacs also included all sorts of additional information, from court dates and mileage between towns to health advice and entertainment. Oxford English Dictionary defines an almanac as a book of charts and tables with a calendar, astrological and meteorological forecasts, and a variety of other information.

By the early 18th century, almanacs in the American colonies provided the traditional calendar-related information as well as entertaining essays, poems, and quotes and advice for the home and farm. Almanacs often included receipts (recipes) for cures for both humans and farm animals, useful household products, food and drink.

“Content marketing” in historical almanacs

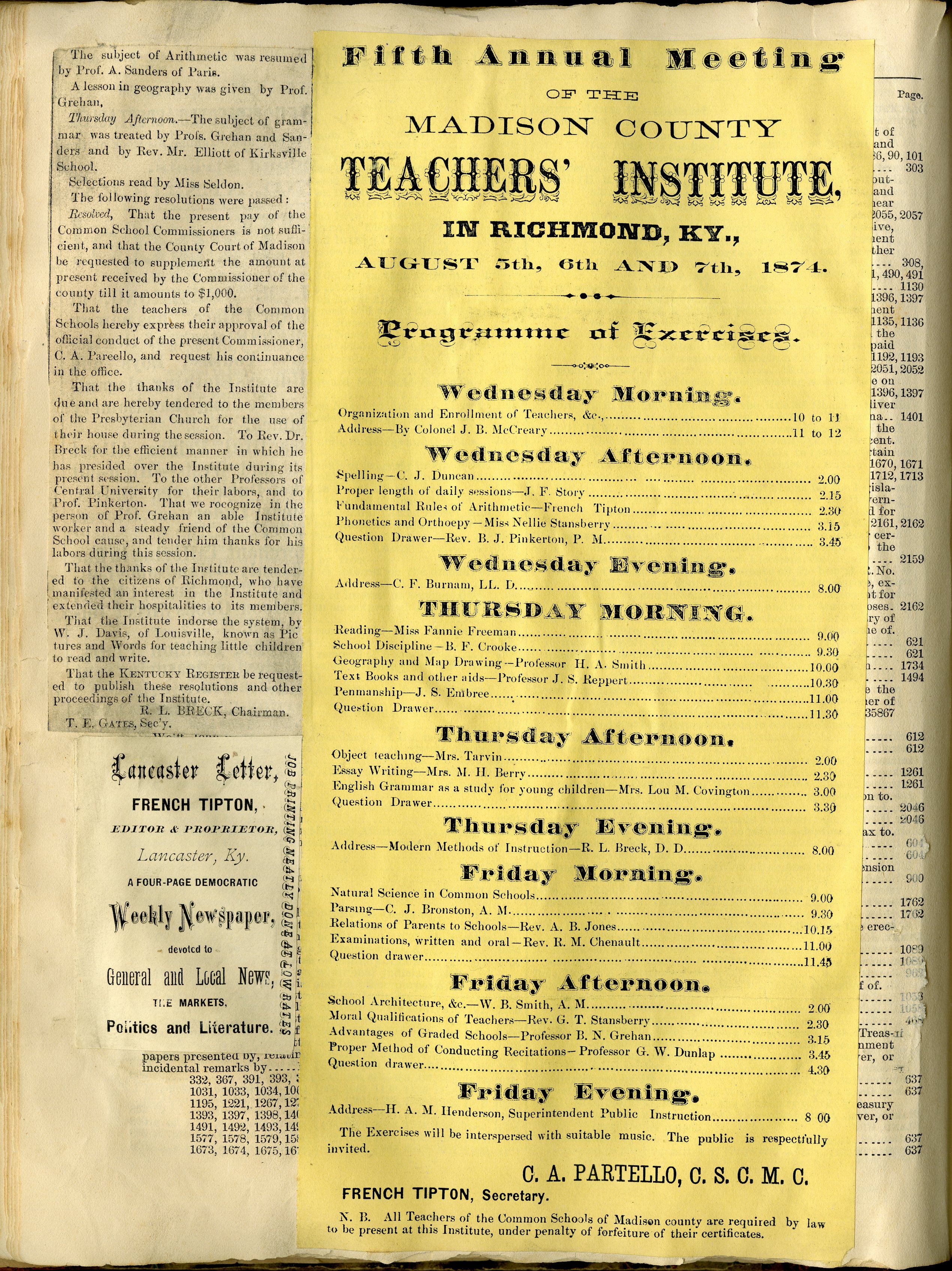

Advertisements began to appear in almanacs as early as the 17th century. By the 19th century, almanacs full of essays, advertisements, and customer testimonials were printed and distributed free or cheap to sell medicine, food, and other products. Content marketing, the modern practice of posting informative articles on commercial websites to attract customers and increase search engine rankings (SEO – search engine optimization), isn’t a new strategy. Almanac printers discovered this technique centuries ago.

For example, the 1881 edition of Brayley’s Family Medical Almanac described a wonderful new cure – French Magnetic Oil – and recommended it for numerous complaints. Numerous testimonials from customers (real or fake?) were also included.

As those who comprehend the principles of the action of this remedy have already seen that the list of diseases cured by it is wonderful in number, variety and range: Local Muscular Pains, Growing Pains in Children, Pain in the Side, Back Ache, Cramps in the Limbs, Bunions, Chillblains, and Frost-Bites, Enlarged Veins, Chronic Ulcers, Strains, Cramps, Toothache, Earache, and many others are all comprised in it. (p. 24)

In addition to medical advertising in the form of advice, this 36-page almanac included calendar pages with jokes and funny anecdotes.

-

- We read of a widow who has been three times married. Her first husband was Rob, the second Robins, and the third Robinson. The same door-plate has served the whole three; and the question now is, what extended name can be procured to fill out the remaining space on it.

- A little boy, whose father was a rather immoderate drinker of the moderate kind, one day sprained his wrist, and his mother utilized the whiskey in her husband’s bottle to bathe the little fellow’s wrist. After a while the pain began to abate, and the child surprised his mother by exclaiming ‘Ma, has pa got a sprained throat'” (p. 17)

Almanacs were also published to promote a specific approach to medicine or a cause, such as temperance. In 1841, the author of Prynne’s Almanac noted “We have religious almanacs, political almanacs, phrenological almanacs, comic almanacs, farmers’ almanacs, ladies’ almanacs, pocket almanacs, and temperance almanacs, which last are distributed at our doors without pay, or so much as the requirement of a nod by way of acknowledgment.”1

Crusader’s Almanac (1875) included images, stories, and advice supporting temperance – abstinence from alcohol and tobacco. It also heavily advertised Dr. J. Walker’s California Vinegar Bitters for numerous medical conditions. Bitters were originally a medication composed of alcohol and various botanical ingredients. Dr. Walker’s Bitters were sold as an alcohol-free alternative. Today, bitters are sold not as medication, but as after-dinner drinks and flavorings for cocktails. Translated to 21st-century terminology – this almanac was “content marketing” targeted to supporters of temperance.

Essential Questions / Compelling Questions for the Classroom

Analyze historical media, such as almanacs, in the history classroom to teach media literacy skills (also known as critical analysis or close reading). Challenge your students to consider these essential/compelling questions:

-

- Media have changed over time, but have the messages and strategies really changed?

- Is information framed by advertising automatically “bad” or “unreliable” information? How can we decide?

To learn more about the role of the media in the past and present. . .

- Discovering Quacks, Utopias, and Cemeteries, Modern Lessons from Historical Themes

- Investigating Family, Food, and Housing Themes in Social Studies

- Exploring Vacation and Etiquette Themes in Social Studies

- Resources for teaching media literacy

- Find dozens of full-text historical almanacs on archive.org

Footnotes

- Thomas Horrocks, “Health Advice with An Agenda.” In Popular Print and Popular Medicine: Almanacs and Health Advice in Early America, 90-106. University of Massachusetts Press, 2008. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt5vk32g.9.

3 thoughts on “Almanacs: Information before the Internet”